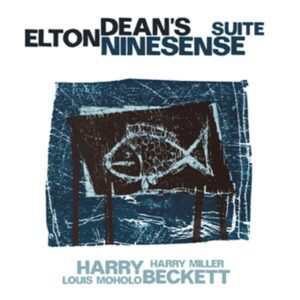

CD jw 107 ELTON DEAN’S NINESENSE & BECKETT / MILLER / MOHOLO

NINESENSE SUITE

ELTON DEAN saxello & alto saxophone

ALAN SKIDMORE tenor saxophone

MARK CHARIG trumpet

HARRY BECKETT trumpet & flugel horn

NICK EVANS trombone

RADU MALFATTI trombone

KEITH TIPPETT piano

HARRY MILLER double bass

LOUIS MOHOLO drums

DE

Konzerte können schnell zu modernen Mythen werden. Weißt du noch, wie wir damals…? Diese Mythen sind Bestandteil individueller Teilhabe, die sich der öffentlichen Bewertung entzieht. Aber was, wenn aus dem Schatten des Mythischen dann doch mal das Dokument heraustritt? Genau dreißig Jahre hallte das Konzert von Elton Dean’s Ninesense allein in meiner Erinnerung nach. Es war ein magischer Moment der Offenbarung, der genau im Augenblick meiner persönlichen Selbstfindung einsetzte. Anfangs zutiefst befremdet, folgte ich diesen neun Musikern, die sich nach meiner innersten Überzeugung ins kollektive Chaos manövrierten. Die Namen Elton Dean, Mark Charig, Keith Tippett

und Harry Miller waren mit Bands wie King Crimson und Soft Machine assoziiert.

Ich war neugierig und wollte sie nicht so leicht davon kommen lassen. Ohne es zu merken, geriet ich in den Sog dieser psychoakustischen Kettenreaktion. Das Chaos sortierte sich, aus der Horde wurde eine Mannschaft, das Individuelle ging in der Gemeinschaft auf, das Ganze leistete wiederum dem Einzelnen Support. Ich konnte überhaupt nicht fassen, wie Elton Dean jede dieser extrem individualistischen Äußerungen auf einem höheren Level zu einer Metasprache verband, ohne dem Einzelnen Gewalt anzutun oder es zu beschneiden. Jedes Element war am richtigen Platz, alles machte Sinn. Diese Aufnahme vom 20. Juni 1981 ist eine Sternstunde der improvisierten Musik.

Sie setzt sich über alle Klischees, Erwartungen und Kanons hinweg, steht ganz für sich selbst, setzt Maßstäbe, die es nur für diesen Augenblick einzulösen galt. Ja, da ist das Chaos und der Urschrei, aber da sind auch unbändiger Swing, frenetischer Rock und bodenloser Blues.

Bei Beckett, Miller und Moholo brechen drei Musiker auf, um ihren gemeinsamen Weg zu erkunden, vom Beginn bis zum Ziel. Beckett schafft an der Seite seiner beiden südafrikanischen Gespielen, die sich mächtig ins Zeug legen, das

Außerordentliche. Er zieht alle Register, Miller und Moholo garantieren ihm indes eine derart dichte Klangumgebung, dass die Musik oft nach viel mehr als einem Trio klingt. Dieses Konzert ist eine Offenbarung des Äußersten. Wie weit können wir in dieser Konstellation gehen? Und sie gehen weit, sehr weit, immer weiter und kommen ans Ziel. Auch dies ein historischer Augenblick. Dokumente können manchmal eben doch voller Segen sein! Wolf Kampmann

EN

Prime, hitherto-unreleased slices of Jazz’s past, these CDs not only bring into circulation historically important live performances, but also confirm the skills of featured percussionist Louis Moholo-Moholo. One of the last surviving members of the many South African improvisers who left the country in the early 1960s because of Apartheid, Moholo, 71, still plays in fine form, and has returned to live in South Africa.

In 1979, 1981 and 1982 when these sets were recorded, Moholo – who added the second “Moholo” to his name following his mother’s death – and other SA expats were involved in different situations. No longer part of the cohesive Blue Notes band with which he had arrived in England in early 1960s, some players such as Moholo and saxophonist Dudu Pukwana regularly joined with pioneering British free improvisers in groups such as Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, led by another ex-Blue Note, or other formations such as saxophonist Elton Dean’s Ninesense represented here. Meanwhile bassist Johnny Dyani, another former Blue Noter had moved to the continent.

Spiritual Knowledge And Grace is particularly noteworthy since Pukwana, Dyani and Moholo are captured on a rare one-off gig in a Netherlands club with tenor saxophonist Frank Wright. Known as ‚Rev‘ for his soulful playing, Wright was a first-generation New Thinger who had also moved to Europe for greater opportunities. The second CD is another matter entirely. Recorded at 1981’s Jazzwerkstatt Peitz, the closest thing to a Woodstock Festival that existed in what was then East Germany, the first track is an over-40 minute suite with Moholo’s drums powering a group of some of the era’s most accomplished British Freeboppers. Recorded at the same location the next year, Natal is different still. Here the drummer is part of bare-bones trio with two other United Kingdom-based expatriates: Barbados-born trumpeter Harry Beckett (1935-2010) and Cape Town-native, bassist Harry Miller (1941-1983).

With Miller and Beckett taking centre stage with elongated grace notes from the trumpeter and cerebral string-set anglings and staccato extensions from the bassist, the drummer’s chief function is encouragement; both percussively and verbally. Slightly older than the others, Beckett’s roughened grace notes, peeps and squeals are never less than tonic. He splutters out intense improvisational tropes throughout, but without straying too far from the melody. Miller on the other hand varies his slaps, walking and jabs with quick-popping and sul tasto scrubs. While operating in double counterpoint with the trumpeter, his technique reflects four-string advances that had taken place during the proceeding decade. Contributing to coloration and rhythmic thrust are Moholo’s drums, a presence every step of the way.

The drummer’s rhythmic skill is stretched even more on the two half-hour plus selections which make up Spiritual Knowledge And Grace. That’s because his beat is the only constant as the others introduce new textures throughout by switching instruments. Wright as well as Dyani plays bass at points, while both Dyani and Pukwana contribute piano patterns when needed. This multi-instrumentalism become particularly problematic during the nearly 40-minute Contemporary Fire, when the South Africans begin encouraging one another – tongue clicking and chanting – in Xhosa, although it does mean that the Tranesque reed overblowing heard is from the American. Wright’s disconnected tenor saxophone punctuation plus high-frequency squeals and flutters also improvise in tandem with similar tone extensions from Pukwana’s alto saxophone with each man reaching for higher-pitched notes as Dyani pounds piano variations behind them. It’s also Wright who most likely adds a trebly, diaphragm vibrated blues-swing line to his playing, tossing in split-second quotes as he trades off with the altioist, each offering staccato variation on the initial theme.

On his own Dyani offers tough flamenco-styled plucks, multi-fingered runs and arco slides, as Pukwana creates pressurized key-clipping piano runs and Wright wraps up with characteristic Gospel-and-Bop vibrations. Earlier his renal sax ejaculations contrast markedly with the altoist’s chromatic squeals. While the interacting reed trills may call to mind other tenor-alto partnerships like John Tchicai and Archie Shepp, here, at least, Wright glossolalia and split tones confirm that this native of the Southern U.S. may have been more influenced by musical voodoo then the native of Southern Africa who had closer knowledge of witch doctors. When the horns decorate the initial theme with intense phrases at different lengths, Dyani’s thumps and sul ponticello strains plus Moholo’s press rolls and cymbal accents keep the ragged interface from splintering and vanishing into the stratosphere.

Fortissimo layered solos from the six horns, alone and in teams, presents a similar organizational challenge on the other CD. But at least the vibrated reed lines and exploding grace notes from the brass are kept down to earth by a full rhythm section. Solid in his pacing as he is inspired in his soloing, Miller thickens the beat as much as Walter Page with the Basie band or Bill Crow with the Concert Jazz band would have done in similar circumstances. As for pianist Keith Tippett, the former-and-future experimenter sounds appropriately grounded. Throughout, he sluices from metronomic pulsing and merry-go-round key splatters to motivated single-note comping that could have come from Count Basie’s keyboard. As for the horns, multiphonic hocketing, animalistic shrieking and discordant vibrations share space with more common swing motifs. The frequent stop-time sections also give ample space to reed splatters, trombone guffaws, one mellow trumpet aside – from Beckett? – split tone squeals from Dean’s saxello alongside linear reed blending and brass fluttering.

Eventually a climax is reached once Alan Skidmore’s intense tenor saxophone solo and key-clipping from Tippett gives way to verbalized cat calls and retches from the band members, pushing the cacophonous call-and-response section work to a satisfying conclusion.

When the inspirational playing from the dozen players represented on both CDs is matched with the novelty of hearing these previously unknown sessions, it makes both valuable additions to all-encompassing collections of European contemporary Jazz. Ken Waxman